Polygamy is a Biblical concept that was approved by God only when commanded by Him to serve His purposes. At all other times, traditional marriages with one husband and one wife is the standard marriage format approved for us on Earth. In the Old Testament, we see a number of marriages involving polygamy, including Abraham’s marriage to his wife’s handmaiden in order to produce an heir. Jacob had multiple wives and the prophet Samuel was the result of a marriage of polygamy. There are Biblical instructions for the treatment of women who were expected to marry their brothers-in-law after the deaths of their own husbands in order to produce heirs for the deceased husband, even if the brother was currently married.

Mormons, a nickname for members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, practiced polygamy in the early days of the church, but have not done so for more than 100 years. Polygamists who call themselves Mormons are not members of the LDS Church and anyone who is a member and begins to practice is excommunicated. This is not a time set aside for such practices.

Mormons, a nickname for members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, practiced polygamy in the early days of the church, but have not done so for more than 100 years. Polygamists who call themselves Mormons are not members of the LDS Church and anyone who is a member and begins to practice is excommunicated. This is not a time set aside for such practices.

Polygamy as practiced in the 1800s was very different than the polygamy often practiced by modern fundamentalist groups. In early Mormon history, it was a minority practice, with only about one-third of adult women involved in polygamous marriages. About one-third of those women were divorced or widowed previously, suggesting they sought financial and emotional support for themselves and their children. The majority of marriages with multiple wives had only two wives.

Unlike some modern groups, pioneer Mormons were not assigned wives, nor could wives be taken from them. If a man wished to take on a second wife, he first had to pray to make sure this was what God expected of him. More often, it came to him through personal revelation and frequently, the revelation came through current wives. Then he needed the permission of his first wife. Without that, he could not marry again. Next, he had to obtain permission from the woman he wanted to marry, who was free to accept or reject as she chose. Finally, he had to be given permission from the church, in order to demonstrate he could support an additional wife and children, that he was a good church member, and was known as a good husband.

Some women who entered into a celestial marriage, as they were often called, found they simply could not adjust to the situation. If this happened, Brigham Young granted the woman a divorce, even though divorce is normally frowned upon except under specific circumstances, such as abuse. However, men who found they could not adjust were not granted divorces. They were reminded that they had initiated the marriage and had a responsibility to the new wife. Men in this condition were told to return home and work harder.

Many Mormon women were puzzled that the world found their situation degrading, since they did not. Eliza R. Snow, one of Brigham Young’s wives, said in a meeting on women’s rights:

Our enemies pretend that, in Utah, woman is held in a state of vassalage—that she does not act from choice, but by coercion. What nonsense!

I will now ask of this assemblage of intelligent ladies, Do you know of any place on the face of the earth, where woman has more liberty and where she enjoys such high and glorious privileges as she does here as a Latter-day Saint? No! the very idea of a woman here in a state of slavery is a burlesque on good common sense . . . as women of God, filling high and responsible positions, performing sacred duties—women who stand not as dictators, but as counselors to their husbands, and who, in the purest, noblest sense of refined womanhood, are truly their helpmates—we not only speak because we have the right, but justice and humanity demands we should! (See Jaynann Morgan Payne, “Eliza R. Snow: First Lady of the Pioneers,” Ensign, September 1973.)

Mormon women knew they had more freedom and rights than most women in the country at that time. Until the federal government disenfranchised them, Mormon women had the right to vote in local elections. Brigham Young encouraged many to have careers, even those outside the traditional fields open to women in their day:

As I have often told my sisters in the Female Relief Societies, we have sisters here who, if they had the privilege of studying, would make just as good mathematicians or accountants as any man; and we think they ought to have the privilege to study these branches of knowledge that they may develop the powers with which they are endowed. We believe that women are useful not only to sweep houses, wash dishes, make beds, and raise babies, but that they should stand behind the counter, study law or physic [medicine], or become good book-keepers and be able to do the business in any counting house, and this to enlarge their sphere of usefulness for the benefit of society at large (Discourses of Brigham Young, 216–17).

When there were multiple wives, there was often one wife willing and enthusiastic about caring for the children and the home. In these cases, President Young told the other wives they should consider returning to school for more education or taking on a career. He encouraged many women to study medicine and in time, the Mormons boasted many women who went east to become doctors in a time when women were struggling to be admitted to medical schools. The new doctors trained midwives and nurses and eventually, the women’s auxiliary, the Relief Society, opened its own hospital to put those talents to work.

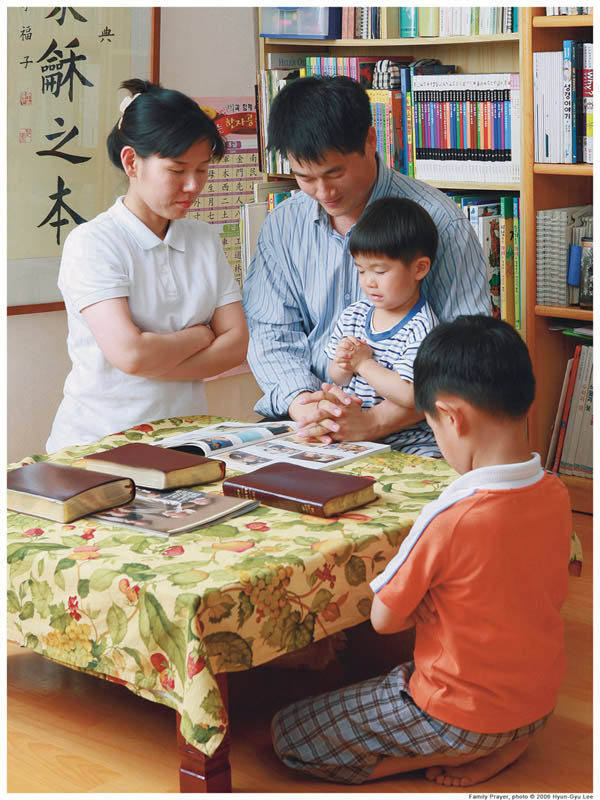

This freedom, so limited for the majority of women, may be one reason many women enjoyed being part of a celestial marriage. Another is that in the early days of the church, married men were sent on missions for several years at a time. (Today, younger missionaries are unmarried and older ones serve with their spouses.) Having an additional wife in the home provided adult companionship and help with the chores and finances. Since it meant one wife could take employment or two adults were available to do farm work, the family lived more comfortably during these missions. Of course, women were also enthusiastic about taking on challenging roles when asked to do so by God, and the spiritual motivation was the primary factor in these families.

Although polygamy is no longer a part of the Mormon experience, it played a number of critical roles in early church history. As with the practice in ancient times, polygamy can be a beneficial practice—when God calls for it.